Iron rich asteroid strength may be far greater than scientists previously believed, according to a groundbreaking experiment that simulated extreme impact conditions on real meteorite material. The findings could significantly reshape how Earth prepares for potential asteroid threats in the future.

Researchers subjected an iron meteorite to intense radiation at CERN, revealing that metal-rich asteroids can absorb enormous amounts of energy without breaking apart — and may even grow stronger under stress. The study offers new insight into how near-Earth objects behave during atmospheric entry or deflection attempts.

Understanding the Risk from Near-Earth Asteroids

Our solar system contains countless small rocky bodies, many of which occasionally pass close to Earth. These objects, known as Near-Earth Objects (NEOs), include asteroids and comets whose orbits bring them into Earth’s neighborhood.

Scientists currently track more than 37,000 near-Earth asteroids and over 100 near-Earth comets, though estimates suggest millions may exist. Among them, Potentially Hazardous Objects (PHOs) receive special attention due to their size and proximity to Earth.

While experts say no known PHO poses an immediate threat within the next century, planetary defense experts agree that understanding asteroid behavior is essential before a real emergency arises.

Lessons from NASA’s DART Mission

In 2022, NASA successfully demonstrated asteroid deflection with the Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART). The mission deliberately crashed a spacecraft into Dimorphos, a small moonlet orbiting the asteroid Didymos, slightly altering its orbit.

The mission proved that kinetic impactors could change an asteroid’s path. However, it also raised a critical question: how do different asteroid materials respond to extreme forces?

That question lies at the heart of the new research into iron-rich asteroid strength.

Simulating an Asteroid Impact at CERN

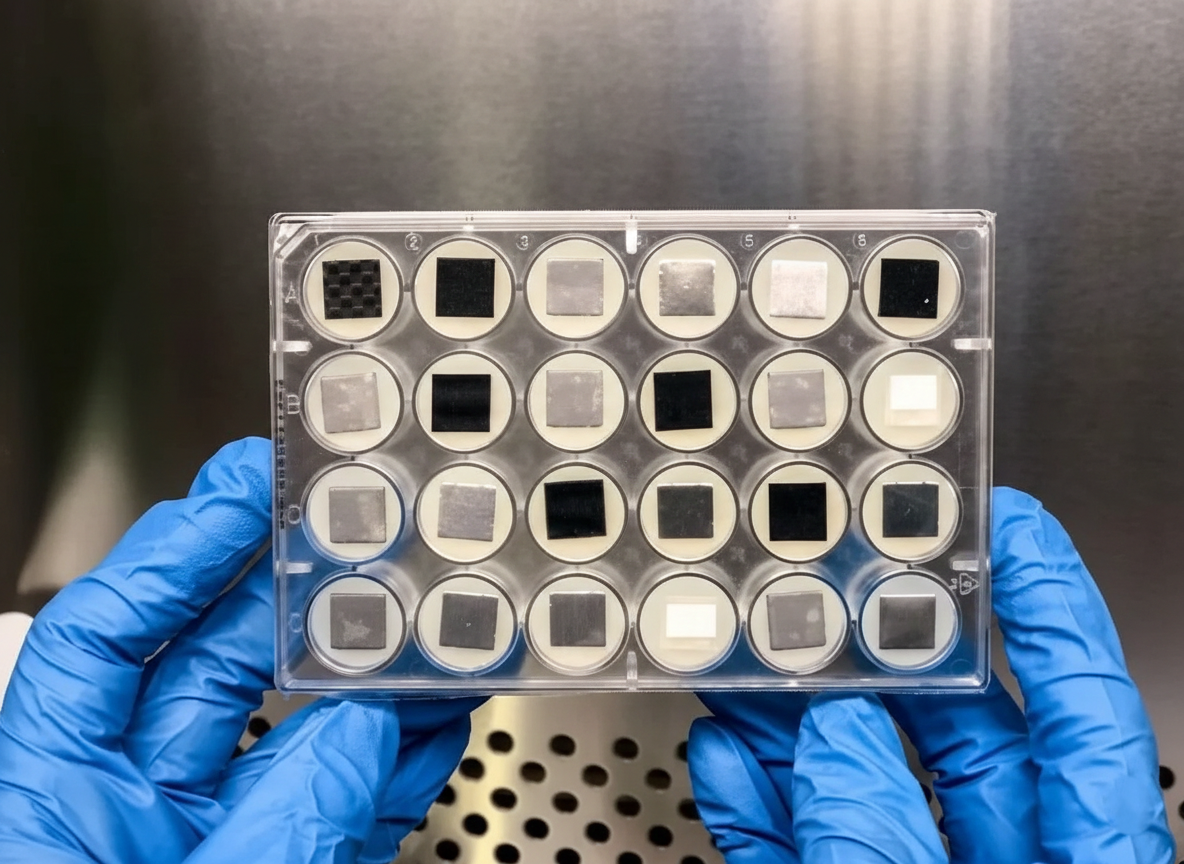

To investigate, an international research team turned to CERN’s High Radiation to Materials (HiRadMat) facility in Switzerland. Instead of simulations alone, scientists tested a real piece of space rock — the Campo del Cielo iron meteorite, which fell to Earth thousands of years ago.

The meteorite sample was bombarded with 440-giga-electron-volt proton beams, recreating stresses similar to those experienced during atmospheric entry or asteroid deflection attempts.

Using Doppler vibrometry, the team measured microscopic surface vibrations in real time, allowing them to observe how the meteorite responded internally as stress levels increased.

Unexpected Results: Strength That Increases Under Stress

The results surprised researchers. Instead of cracking or fragmenting, the iron meteorite absorbed significantly more energy than expected. Even more striking, it dissipated energy more efficiently as stress increased.

This suggests that iron-rich asteroid strength is not static. Instead, the internal structure of metal-rich asteroids appears capable of redistributing stress in complex ways, much like advanced composite materials engineered on Earth.

Rather than shattering, these asteroids may channel energy deeper into their interiors without breaking apart.

Challenging Long-Held Assumptions

For decades, planetary defense models assumed that large impacts or explosive forces would easily fragment asteroids. Those assumptions were partly based on observations of meteors breaking apart in Earth’s atmosphere and static laboratory tests on meteorite samples.

However, the new findings challenge those models.

According to the researchers, the discrepancy can be explained by the heterogeneous internal structure of meteorites — a mix of metals, fractures, and crystalline regions that interact dynamically under stress.

As Professor Gianluca Gregori of the University of Oxford explained, this marks the first time scientists have directly observed how a meteorite deforms, strengthens, and adapts in real time under extreme conditions.

Implications for Planetary Defense

The discovery has major consequences for how humanity might one day prevent an asteroid impact.

If iron-rich asteroids are tougher than expected, simple kinetic impacts may not be enough to break them apart — and fragmentation could even be counterproductive, creating multiple dangerous objects instead of one.

Instead, future deflection strategies may need to focus on controlled momentum transfer, delivering energy in ways that move an asteroid without shattering it.

Understanding iron-rich asteroid strength could help engineers design more effective planetary defense missions that push hazardous objects safely off course.

Why Metal-Rich Asteroids Matter

Not all asteroids are alike. While many are rocky or carbon-rich, M-type asteroids, which are rich in iron and nickel, represent some of the densest and most resilient bodies in the solar system.

These asteroids are also of scientific and economic interest due to their metal content. But from a defense standpoint, their durability makes them especially important to study.

This research suggests that metal-rich asteroids entering Earth’s atmosphere may survive longer and penetrate deeper than previously thought, increasing their potential danger.

A New Era of Asteroid Research

The study highlights the importance of moving beyond computer simulations and static tests. Real-time, non-destructive experiments on actual meteorite material provide insights that models alone cannot capture.

As asteroid detection improves and planetary defense planning advances, data like this will play a critical role in shaping global response strategies.

The findings also underscore the need for international cooperation, as asteroid threats do not respect national borders.

This science report is part of FFRNEWS Astronomy & Space, where cutting-edge discoveries about planetary defense, asteroids, and space science are regularly covered. More space and science updates are available across FFRNEWS’ dedicated science sections.

The original research and reporting for this article were informed by Universe Today, which detailed the CERN experiment and its implications for asteroid deflection strategies.

Universe Today source: