Corrosion proof satellites may soon shift from experimental concept to standard practice thanks to breakthrough materials research at the University of Texas in Dallas. For decades, satellites operating in low Earth orbit (LEO) have battled a surprisingly harsh environment—one where atomic oxygen, high-speed molecular collisions and atmospheric drag combine to shorten mission lifetimes to five years or less. Now, by applying advanced coatings that fight both chemical and physical wear, engineers hope to extend satellite survival, open new orbital regimes and dramatically lower space infrastructure costs.

The hostile environment of LEO

Although space is often described as a “vacuum,” low Earth orbit is far from benign. At altitudes between roughly 95 km and 1,900 km, satellites encounter a thin atmosphere populated by atomic oxygen (O atoms), nitrogen molecules, dynamic UV radiation, micrometeoroids and charged particles. The most insidious agent is atomic oxygen, produced when molecular oxygen is broken apart under ultraviolet radiation. These reactive atoms collide with spacecraft surfaces, chemically binding and causing erosion comparable to rust in extreme environments. Over time, this erodes coatings, degrades structural materials and accelerates orbital decay.

The second major threat is atmospheric drag. Each collision, no matter how tiny, imparts momentum loss. Over weeks and months this adds up, lowering orbital altitude and causing premature re-entry. These two combined threats have meant that many satellites retire far sooner than their designers intended. Against this backdrop, the drive to develop corrosion proof satellites is both timely and crucial.

Breakthrough coatings from UT-Dallas

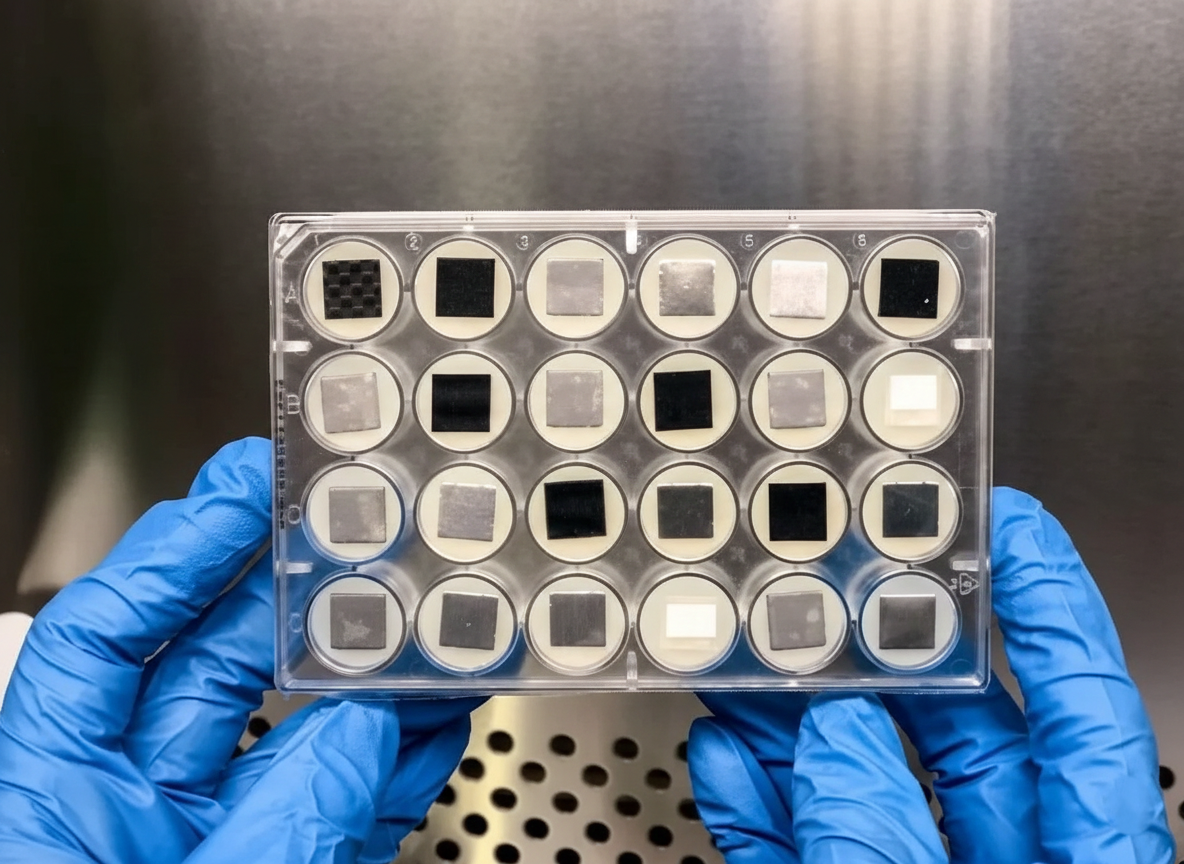

The research team led by materials scientist Rafik Addou is applying methods pioneered in microelectronics and optics to build next-generation coatings. Their dual approach uses atomic layer deposition (ALD) and sol-gel processing:

- Atomic layer deposition (ALD) allows materials to be built up one atomic layer at a time. This gives unprecedented control over thickness, uniformity and bonding—key when fabricating coatings to resist atomic oxygen attack.

- Sol-gel processing creates glass- or ceramic-like materials from liquid precursors, enabling the formation of ultra-smooth surfaces that minimize drag and provide high durability.

In controlled laboratory tests mimicking extreme atomic oxygen fluxes, the coatings developed at UT-Dallas exhibited notably superior resilience, significantly reducing erosion compared with current materials. The implication: satellites treated with these coatings may survive in harsher orbits, with fewer maintenance requirements.

Why this matters for new orbital zones

One of the most promising impacts of corrosion proof satellites is access to very low Earth orbit (VLEO)—altitudes below roughly 350 km, traditionally avoided due to intense drag and molecular collisions. VLEO offers advantages: lower latency for communications, improved imaging resolution, lower launch energy and reduced signal delay. But the material environment has made operations costly and short-lived. With new coatings, spacecraft could operate longer in VLEO, making mega-constellations more sustainable, enabling persistent Earth monitoring and opening areas of the orbital market hitherto inaccessible.

Impact on satellite economics and sustainability

The viability of commercial satellite constellations—including Earth observation, communications and space-based services—depends on cost, durability and launch frequency. Traditional satellite replacement cycles every 5–7 years incur high launch and build costs. By enabling corrosion proof satellites, the industry could reduce churn, lower costs, and support a greener orbital ecosystem (fewer launches, less debris).

Additionally, longer mission lifetimes reduce the need for frequent orbital replacements and reduce risk of derelict satellites turning into debris. In a time when space-traffic management is emerging as a major concern, materials that prolong service life have clear environmental benefits.

Challenges and next steps

Despite promising results, several hurdles remain before corrosion proof satellites become standard:

- Space-qualification: Lab performance must be validated in orbit. Long-term exposure to vacuum, radiation, thermal cycling and micrometeoroid impacts require rigorous testing.

- Integration: Coatings must be compatible with diverse satellite structures, solar panels, antenna surfaces and thermal control systems.

- Cost vs benefit: For small satellites (CubeSats), added coating costs must be justified by extended mission life or improved performance. For large satellites, the return is clearer, but timelines are long.

- Orbit-specific adaptation: Different orbits have different material stressors. A coating optimized for VLEO may differ from one for geostationary orbit or interplanetary craft.

UT-Dallas is preparing to test a prototype coating in an actual CubeSat mission, deploying from the International Space Station’s Kibō module. If successful, the coatings could revolutionize satellite design within the next 3–5 years.

Broader significance for human spaceflight and technology

The innovations in corrosion protection have parallels in human spaceflight, moon bases and Mars habitats. Materials that resist atomic oxygen and atmospheric drag are also beneficial for habitats in low Earth orbit, lunar orbit or low-altitude Mars orbit. Techniques developed for corrosion proof satellites may influence future spacecraft, human habitats and long-duration missions.

Beyond space, these material science advances may benefit Earth-based industries: aerospace, high-altitude vehicles, high-temperature chemical processing and even infrastructure in extreme environments like the Arctic.

The field of corrosion proof satellites marks a shift in how engineers approach space longevity. Rather than accepting limited lifetimes, researchers are proactively designing materials to thrive in harsh orbits. If successfully deployed, these coatings could transform satellite economics, open new orbital zones and support sustainable space operations for decades to come. The next frontier isn’t just about reaching space—it’s about staying there, performing reliably, and doing so in places once thought too hostile to attempt.

Source: Universe Today