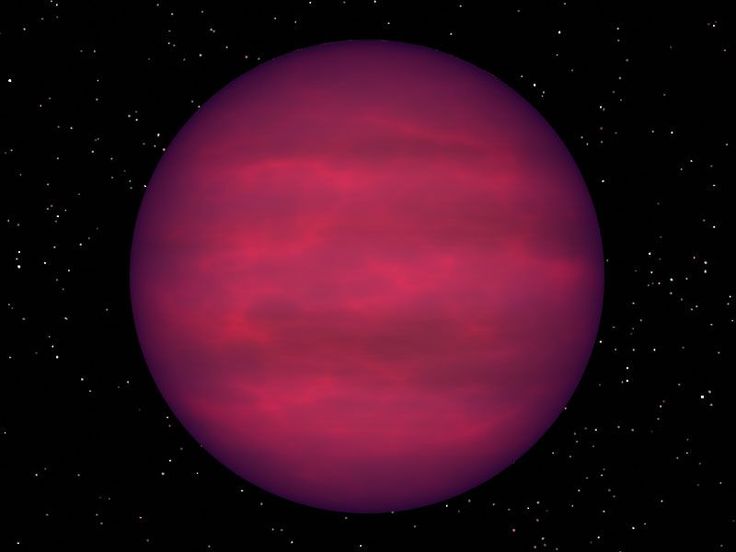

Phosphine in Brown Dwarf Atmosphere has been discovered for the first time — a groundbreaking achievement made possible by the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST). This marks a historic leap in understanding the chemistry of brown dwarfs — mysterious “failed stars” that lie between planets and full-fledged stars.

A Discovery That Redefines Cosmic Chemistry

For decades, astronomers suspected that phosphine in brown dwarf atmospheres could exist, but until now, it had never been observed. The detection of phosphine (PH₃) in Wolf 1130C, a low-metallicity brown dwarf located in our galaxy’s thick disk, confirms theories about how metallicity shapes atmospheric composition.

Using JWST’s NIRSpec instrument, researchers identified a distinct absorption feature around 4.3 micrometres, a spectral fingerprint unique to phosphine. This discovery reveals that even faint, distant brown dwarfs can harbor complex chemical signatures once hidden from older telescopes.

Why Metallicity Matters in Brown Dwarfs

In astronomy, “metallicity” refers to the fraction of elements heavier than hydrogen and helium present in a star or brown dwarf. Low-metallicity brown dwarfs like Wolf 1130C are ancient objects — cosmic relics formed when the universe contained fewer heavy elements.

Because metallicity affects how gases mix and react, it directly influences whether molecules like phosphine or carbon dioxide (CO₂) dominate an atmosphere. High metallicity often means more CO₂, which can mask weaker compounds like phosphine.

The Hidden Chemistry of Phosphine

Gas giants such as Jupiter and Saturn are rich in phosphine because their cooler upper atmospheres prevent CO₂ from forming in large quantities. This makes phosphine easy to detect in their spectra.

However, brown dwarfs are warmer, and most of their carbon is locked into CO₂, which absorbs light at the same wavelengths as phosphine. That overlap hides the phosphine signal — unless, as in Wolf 1130C, the brown dwarf’s low metallicity means there isn’t much CO₂ in the first place.

This is why phosphine in brown dwarf atmospheres has been so elusive — it was always there, just buried beneath stronger signals.

The Source of the Phosphine

Researchers confirmed that the detected phosphine in Wolf 1130C’s atmosphere was produced internally, not inherited from its nearby companion stars. The compound likely forms deep within the brown dwarf under extreme pressure and heat, before rising into the outer layers where JWST could detect it.

This self-generated chemical process strengthens the theory that phosphine is an intrinsic atmospheric product of some low-metallicity brown dwarfs.

Implications for Exoplanets and Biosignatures

The discovery of phosphine in a brown dwarf atmosphere carries huge implications for astrobiology and exoplanet studies. On rocky planets like Venus, phosphine might hint at biological activity — but in gas giants and brown dwarfs, it’s produced abiotically through pure chemistry.

This means scientists must be cautious when interpreting phosphine detections elsewhere as signs of life. The overlap between phosphine and CO₂ absorption lines can easily create false positives in exoplanet research.

Still, this detection helps astronomers refine what truly counts as a biosignature — improving how future missions search for life beyond Earth.

Wolf 1130C: A Cosmic Time Capsule

Wolf 1130C, roughly 44 times the mass of Jupiter, represents an ancient class of low-metallicity brown dwarfs that formed billions of years ago. Studying such objects helps astronomers trace how the chemical makeup of the galaxy evolved over cosmic time — from hydrogen-rich beginnings to today’s complex molecular diversity.

James Webb’s Role in the Breakthrough

The James Webb Space Telescope made this first-ever detection of phosphine in a brown dwarf atmosphere possible. Its infrared capabilities allow it to isolate subtle molecular signals even in faint, distant targets that older telescopes couldn’t resolve.

This achievement proves JWST’s power as a cosmic chemist, capable of detecting the fingerprints of elements and molecules across the universe — even in the most extreme and ancient environments.

End of Obscurity, Dawn of Discovery

The detection of phosphine in a brown dwarf atmosphere marks a new chapter in astronomical science. It reveals that these mysterious “failed stars” are more chemically diverse than once believed and that even hidden molecules can tell powerful stories about the universe’s past.

Future JWST observations may find phosphine in other low-metallicity brown dwarfs, confirming that what we’ve uncovered in Wolf 1130C is only the beginning of a far deeper cosmic chemistry waiting to be explored.

Source: Universe Today

6un2lq