In 1978, a new era dawned at NASA with the announcement of 35 new astronauts for the burgeoning Space Shuttle program. What made this class historic was not just the new technology they would be flying, but the fact that six of them were women. This groundbreaking cohort included Sally Ride, Judy Resnik, Anna Fisher, Kathryn Sullivan, Shannon Lucid, and Rhea Seddon. Their inclusion marked a pivotal moment, as the Space Shuttle program, by opening its selection criteria beyond military pilots, finally began to chip away at NASA’s long-standing gender bias. The story of these trailblazing women Space Shuttle astronauts is one of resilience, humor, and a quiet revolution that reshaped the future of space exploration.

The path to space for these women was filled with unique challenges, many of which were rooted in a culture unaccustomed to female presence in such a high-stakes field. From the comical to the condescending, these experiences highlight just how much of an “all-male club” space travel had been. The infamous “Female PPK” (Personal Preference Kit), a collection of cosmetics provided to the women, was a prime example of this disconnect. While some, like Rhea Seddon, found the make-up practical for in-flight photos, others, including Kathryn Sullivan, were more annoyed. As Sullivan noted, it suggested that someone believed they might be “less mission-focused than our male counterparts,” a stereotype they were determined to disprove.

The struggles went beyond cosmetics. The NASA supply chain had never prepared for women’s specific needs. Astronauts were given gold-plated tie clips and cufflinks as souvenirs, and even a simple task like providing sanitary products for a mission proved to be a comical misstep. As Kathryn Sullivan recalled, a NASA engineer once presented Sally Ride with a string of 100 tampons for a one-week mission, leading to a moment of shared laughter. These “innocent gaffes” were a testament to the fact that while NASA had the engineering prowess to reach for the stars, it had much to learn about the human element of diversity.

Redefining “The Right Stuff”

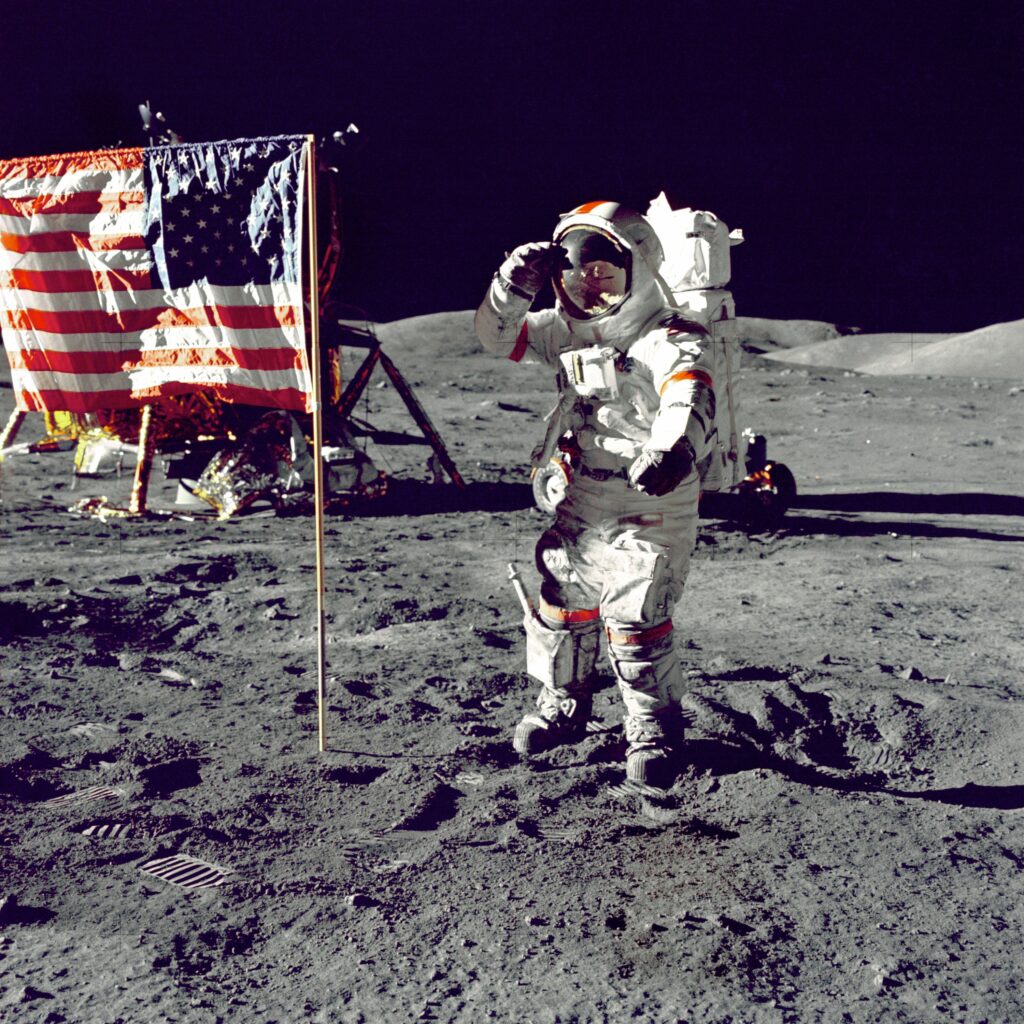

Historically, “the right stuff” for a NASA astronaut was synonymous with being a male military pilot. The Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo programs had all been dominated by men with a background in flying high-performance aircraft. The Space Shuttle, however, was different. It required a new kind of astronaut: the “mission specialist.” These individuals, with backgrounds in science, medicine, and engineering, were crucial for operating the Shuttle’s complex systems and performing experiments in space. This change in criteria was the crack in the glass ceiling that allowed the first class of women Space Shuttle astronauts to enter the program.

Even with their immense qualifications—including doctorates, extensive research experience, and a fierce determination—their inclusion was met with a degree of skepticism from both the public and some of their male colleagues. Astronaut Mike Mullane, a veteran pilot who came from an all-male military academy, admitted to his initial misgivings about how these scientists and women would adapt to a world so different from his. However, as he later admitted, it didn’t take long to realize that these new astronauts brought invaluable skills and a fresh perspective. Mullane’s relationships with his female colleagues evolved from suspicion to respect, a testament to their professionalism and dedication.

The Influence of Nichelle Nichols and a Lasting Legacy

The inclusion of the first women Space Shuttle astronauts was no accident; it was the result of a deliberate effort by NASA to rectify its long-standing diversity issues. Following a critical report in the early 1970s that deemed the agency’s hiring of minorities “a near total failure,” NASA made a concerted effort to broaden its recruitment. To achieve this, they enlisted the help of a powerful cultural icon: Nichelle Nichols, who played Lieutenant Uhura in the original Star Trek series. Nichols’ presence on the bridge of the starship Enterprise had a profound impact on a generation of women and people of color, and her recruitment videos for NASA encouraged a new pool of applicants. Her influence was so significant that Mae Jemison, the first black woman in space, and astronaut Judy Resnik both cited her as a key inspiration.

The legacy of the first women Space Shuttle astronauts extends far beyond their initial missions. Their trailblazing efforts paved the way for a truly diverse space agency. Today, NASA is a completely different organization, with mission specialists like Loral O’Hara and Jasmin Moghbeli continuing the tradition of excellence. These modern astronauts are a powerful reminder that “the right stuff” is no longer the preserve of one specific demographic. As journalist Lynn Sherr, author of a biography on Sally Ride, put it, “Sally’s position was it took NASA 20 years to get there but, once they made the decision to include women and minorities, they were all in.” Sally Ride herself saw NASA as “the equal opportunity employer it had finally become.”

The journey of these first women Space Shuttle astronauts was not always easy, but their determination helped transform NASA from a boys’ club into a truly inclusive institution. Their story is a powerful reminder that progress often requires breaking down barriers, challenging stereotypes, and having the courage to venture into the unknown, both in space and on Earth.

m6qzbe